A Classic Fighting and Utility Design Made into a Gentleman’s Folder

I don’t normally go in for classy knives, but if nothing else, the LionSteel Gitano was good for turning me onto navaja style knives. That’s a big piece of knife history I was largely unaware of until I looked into the inspiration behind the Gitano’s design. The fact that my first instinct after a paper test was to go read up on a bunch of history should also be a strong indication that this is doing its job well as a gentleman’s folder.

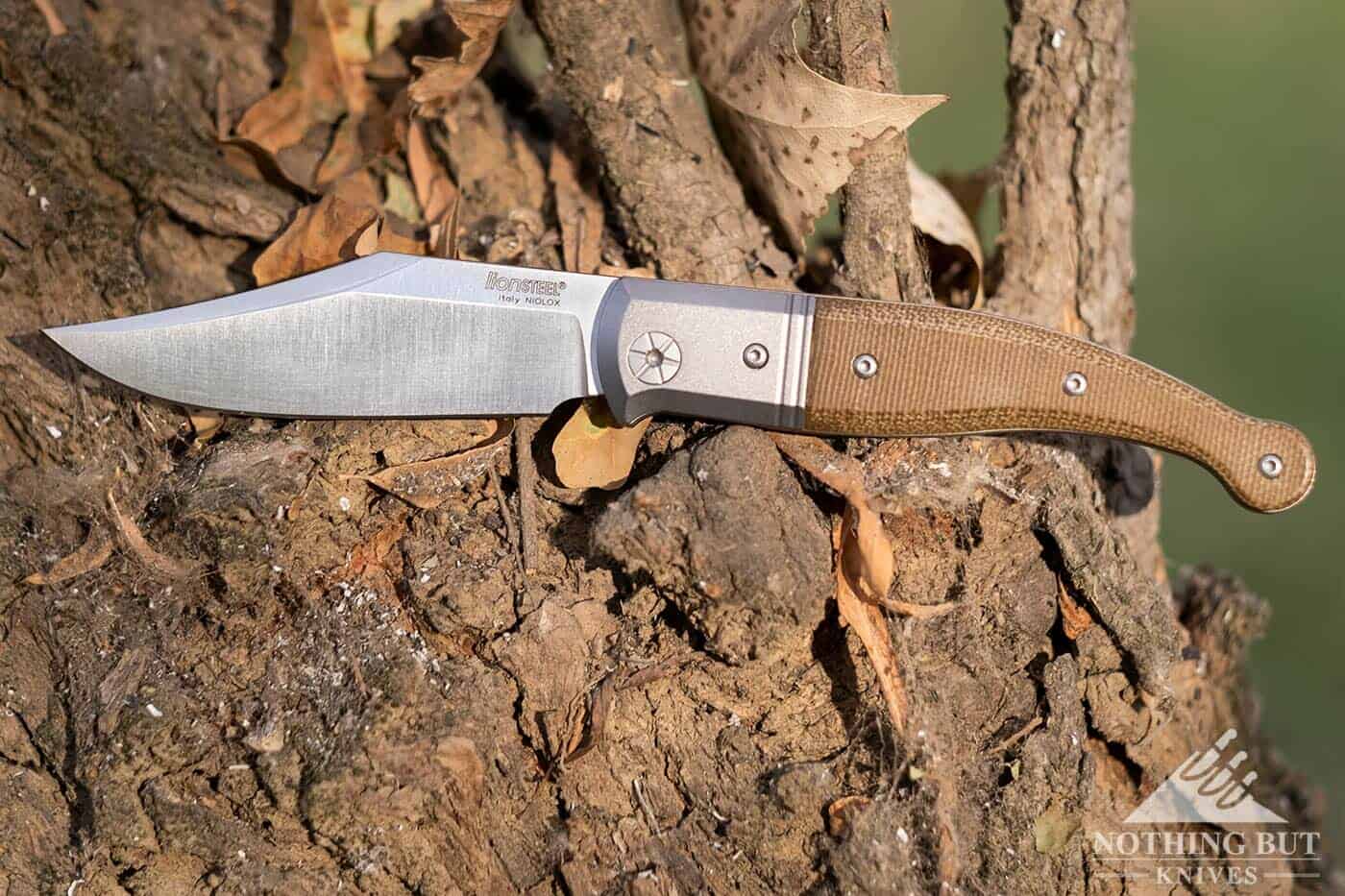

LionSteel always excels at making knives that just look great, and this one is a collaboration with Dutch designer Gudy Van Poppel, who also has a knack for making odd but fancy things (the little stick figure next to an “L” on the blade is the symbol of his company POP-L).

But there’s also a lot of good to be said about the ergonomics and overall look of this knife; not just its cool history. This thing looks good, feels comfortable in the hand and has a picture-perfect clip point blade with a mean tip that can get a lot of work done even though it’s on a slip joint. There are a lot of little details in the way all the pieces of the design fit and flow together, and it’s one of the more comfortable knives to have in my pocket, in spite of its size.

It does have a glaring issue with the slip joint mechanism that makes closing it a worrisome problem. There are a couple possible fixes for it, but I’ll get into that in more detail later.

Overall, this is a good knife that packs a long, interesting history on its back.

Specifications

| Overall Length: | 7.5″ |

| Blade Length: | 3.5″ |

| Blade Width: | 0.12″ |

| Blade Steel: | Niolox |

| Handle Length: | 4.0″ |

| Blade Shape: | Clip point |

| Blade Grind: | Flat |

| Handle Material: | Micarta |

| Lock Type: | Slip joint |

| Weight: | 2.95″ |

Pros

| Great fit and finish | |

| Rides smoothly in the pocket | |

| Good grind with a well done clip point |

Cons

| Tricky to close |

| Sleek finish isn’t great for the grip |

The History and Designer

I don’t know exactly what inspired Gudy Van Poppel to make this particular design, but I do know it’s based on the navaja style knife that came out of Spain.

The navaja knife has a similar start to the Higonokami knife in that it got really popular because of heightened restrictions on carrying weapons. This design originated in Spain around the 1600’s. Back then it was more of a friction folder, but it saw a dozen different changes over the centuries, especially as it got carried through so many wars (the Peninsula War against Napoleon was particularly formative for the design).

Oddly, its development as a fighting knife started with the people that Van Poppel pulled its name from: the gypsies, or “gitanos”.

It seems weird to me to name this particular iteration after the people who started fighting with this knife, because this feels like anything but a knife for fighting. The tall clip point blade is the only thing that makes it good for that (and God knows the tip is dangerous enough). But everything else from the smoothness of the handle to the lack of any method for fast deployment and especially to the fact that it’s a slip joint, make it very much the opposite of a fighting knife.

And it’s not as if there weren’t other people to pull from in its history. It was popular with farmers as a utility blade as well, but I guess “granjero” doesn’t sound as cool.

The Knife in Action

When the Gitano is open, I enjoy using it. It’s comfortable with a decent enough edge and a vicious point that doesn’t need a lot of pressure to start a hole in something. That last seems like a particularly good feature for a slip joint to have, although it becomes a problem later when you’re trying to close it.

The Blade and Steel

This is the first time I’ve used a knife made of Niolox steel, so I don’t know if this is a great example or not. I can tell you the edge on this knife was pretty good, if not exactly razor sharp. It did fair on a paper test and sailed through cardboard.

As I understand it, Niolox is a Niobium steel, which is supposed to be a lot more fine grained than most others. For example, S35VN is a Niobium steel, although I don’t think the overall performance between the two is comparable. This is supposed to be a highly corrosion-resistant steel with good edge stability, so even though the edge isn’t exactly splitting atoms, it holds up well to use over time.

I like the blade shape immensely. I would like it a lot better on a properly locking knife or a fixed blade, but I think if you made this into a fixed blade you would basically end up with a Spanish-inspired Bowie knife (which I would buy the hell out of). With that in mind, this is a great style of blade. It has plenty of straight edge space for carving or leaning into long cuts on a piece of cardboard, and the severe curve into that sharp point gives the blade a ton of versatility for getting cuts started.

When I say the tip is severe, though, I mean it. It’s also unpredictable until you get used to the way the tip points backward ever so slightly, which, to be fair, is the way a clip point should be. I discovered this when we were cutting labels off of water bottles for testing a completely different kind of knife, and I kept poking holes in the bottles by accident.

Once you’re aware of it, though, you can poke a hole into a lot of things with very little effort. I’ve never really had to apply pressure on something to get a hole started. Just poke the tip in and twist the knife a little, and you’ll be well on your way to creating an indentation in a piece of wood, making eye holes for a sheet or cardboard box (I was mostly carrying this knife during Halloween), or creating a new slot in your belt.

The Handle

This design has really made me appreciate this style of handle. The way it swells into a larger end at the base of the blade gives you more than a enough grip for a folding knife this size, and the small butt makes it ride easily in the pocket. When you’re holding it, you can feel just how well they’ve contoured this handle. There was clearly a lot of care taken to make this knife feel smooth.

They’ve also done a great job making the pocket clip un-intrusive but still useful. It’s small but stiff and seems to be shaped perfectly so that it slides right over the pocket. I don’t really notice any hotspots from it even in a full standard grip. In fact, the only real discomfort I felt from this handle is from my weird ham hands trying to squeeze over the thinned out bottom half. That’s minimal, though, and I don’t notice anything flaring up when I’m using the knife.

Really the only thing I could ask for on this handle is some kind of grippy texture somewhere. I get that some people like that smooth feeling in a handle, especially on a gentleman’s carry, but I’m clumsy and need all the help I can get.

Plus Micarta looks better when the texture comes through anyway.

Looks and Design

Despite my feelings about the smoothness of the Micarta scales, the looks feel like they were a priority on the Gitano. As nice as (almost) everything else on this knife is when you’re using it, the most striking thing about it is how seamless it looks and feels. All the lines are smooth and contoured. Everything is ground to a pleasant rounded edge, and every piece of the knife transitions well into the next part. There isn’t an inch of this knife that doesn’t look and feel good to me.

Except for one big thing…

The Closing Problem

I don’t handle a lot of slip joints, but this one seems especially difficult to close. I understand it’s important to keep the blade from accidentally closing when you’re using it, but I’ve hurt myself more closing this knife than doing anything else with any other knife I’ve ever tested. And that includes the time I misjudged flipping a knife in the air and caught the tip in my finger.

In some sense it’s a good thing. You don’t want a slip joint that’s too easy to close, especially when the tip is as prominent as this. But LionSteel has gone way too far in the other direction.

It took me a long time to start trusting the half stop enough to close it with a hand fully gripped around the handle. I still get nervous, but I have yet to actually close the blade on my hand. All the injuries have come from me trying to work around doing that. A lot of those attempts ended with my left hand slipping into the point of the blade, so I feel like I really need to stress that it’s probably too hard for most people to break that joint without a full grip on the handle. Just pinch the blade, go slow, and trust the half stop.

Loosening the Pivot Screw

The strong joint was almost enough to make me stop carrying the knife altogether until I remembered I have tools and there’s a very prominent torx screw at the pivot point.

So, thank god for Lionsteel. You can help this issue to a degree by loosening up the pivot screw with a T9 torx screwdriver. It’s pretty tough to get started (I very nearly stripped my screwdriver trying), and I wouldn’t suggest loosening it too much since you still need a good amount of resistance to keep the blade usable. But a little bit of a counterclockwise quarter turn will help ease the process.

Grinding the Tab Down

Loosening the pivot screw doesn’t fix the root of the issue, though, which as I understand comes from a combination of the heavy duty spring LionSteel used for the slip joint mechanism, and the size of the tab that locks into the joint on the back piece.

I don’t know that there’s much you can do about that short of grinding that tab down a little. I’ve heard some people have done that with some 100 grit sandpaper and ended up with a much more pleasant experience. I can’t recommend that you do that unless you’re incredibly competent, though. I would try it myself, so I could give you an idea of how to fix this up, but I’m also lazy and mechanically incompetent, so this knife will continue to be a subpar herculean task in my possession.

Alternatives and Comparson

Depending on what kind of handle materials you prefer, this knife can get into the range of $150. The most expensive version has carbon fiber scales, which look nice but detract from the semi-rustic appeal in my opinion. The green Micarta version I tested is on the lower end of the price spectrum, but still over the $100 range. With that said, it’s really important to understand that this knife is as much about being a showpiece as a tool.

There are plenty of other more useful knives you could get. We’re not exactly a gentleman-folder crowd around here, so a lot of the folders I carry day to day (and especially out into the field) tend to be half the usual price of the LionSteel Gitano or overbuilt or stripped down past the point of looking nice in any traditional sense. So the Gitano looks better than most of the pocket knives I own, and there’s something to be said for LionSteel’s impeccable craftsmanship versus what you might get in CRKT’s weird new lineups. But I lean toward knives I won’t feel guilty about beating up, and the Gitano is not that kind of knife.

The point is that the price might be worth it if you like classy slip joints. In the world of gentleman’s folders, even the $150 price tag isn’t that much, and you’re getting a great (if underappreciated) steel and the manufacturing of a company with a stellar reputation. The best slip joint alternative I can recommend is the Kershaw Federalist, which is usually around $50 cheaper and a lot grippier in the handle. It’s on a double detent joint, though, so the lock up strength has the opposite problem of being a little too weak.

If you are looking for a more budget friendly option with a more classic look, the RoseCraft Beaver Creek Barlow may be just the thing.

Conclusion

The main thing holding it back is the tough lock up, which is a pretty serious problem. I love the design and the execution of this knife in every way, but every time I open it up I cringe at the thought of closing it again, and that’s enough to keep it out of my pocket most of the time.

I’ll take it out for a wedding (if I actually like the people getting married), or if I find myself caught up in a riveting conversation about navaja knives. Beyond that, this will stay on my desk. I’ll look out for the day LionSteel comes out with a back lock version.